Ulkokrunni is the largest island in the Krunnit archipelago, about 20 km off Finland’s mainland in the Gulf of Bothnia. Geologically young, around 600 years old, it is still rising at roughly a centimetre a year. New land appears as a raw shoreline, then takes on low vegetation, and eventually closes in with forest. These islands and their skerries were formerly a temporary home in summertime to fishermen, farmers and ship pilots (i.e. the navigators who guided log ships through coastal waters). Now they are part of a privately-owned nature reserve, officially established in 1956 to protect different bird species, including the greylag goose (Anser anser).

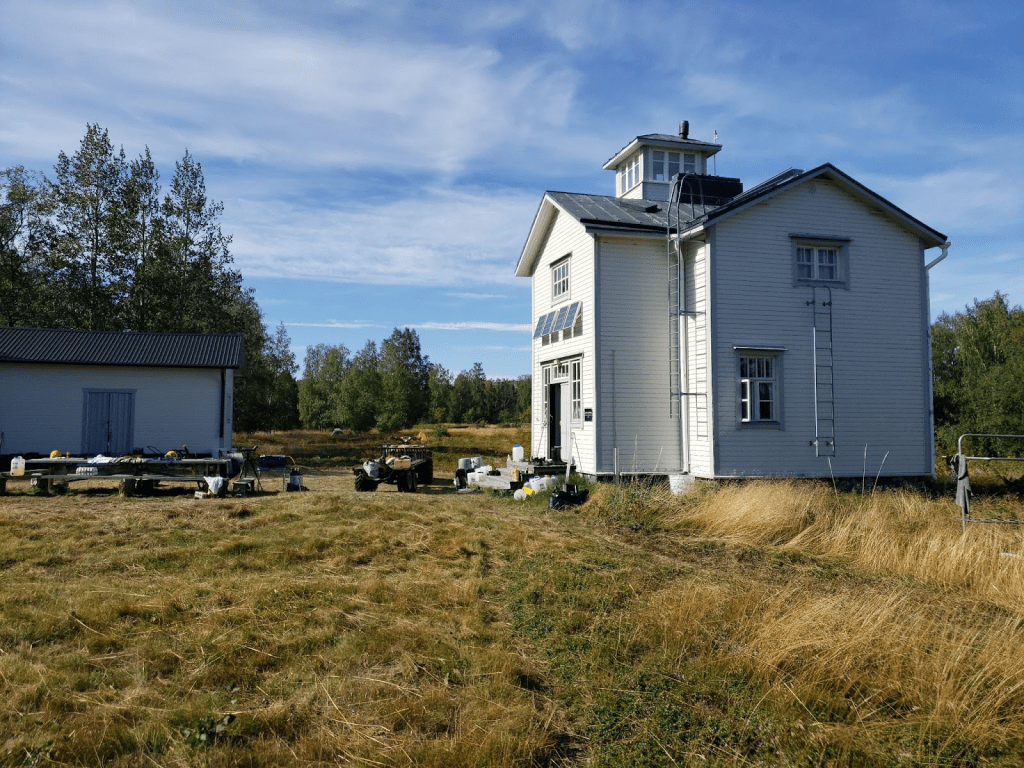

The islands are important stopover sites for migratory birds and support about 60 nesting bird species, as well as the ringed seal. In the northeastern corner of Ulkokrunni stands a small biological research station, originally built in 1872 as a timber ship pilot house, and later repurposed by the University of Oulu in the early 1960s.

On two clear August days, our small group joined the team of the Krunnien Tuki ry (led by Professor Jouni Aspi of the University of Oulu) for their ongoing habitat restoration project. It was fieldwork for SAFIRE, a Profi8 programme at Oulu University focused on trans- and interdisciplinary research on habitat restoration, and for the EU Interreg Aurora funded project NORTHDIVeRSITY, a collaboration between the University of Oulu, Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke) and the Umeå University (Sweden). Leading our fieldwork team was Stefan Prost, Assistant Professor of Biodiversity Genomics at Oulu and head of SAFIRE. He was joined by Martin Grehtlein, a PhD researcher in Oulu’s Biodiversity Genomics Group; Majid Moradmand, a postdoc at the University of Oulu and Associate Professor of Zoology-Biology at the University of Isfahan (Iran); visual artist Arryn Snowball; and myself, Monica Vasile, an environmental anthropologist-historian working as part of the SAFIRE project at the Department of Cultural Anthropology at Oulu. Different disciplines, different toolkits, but the same purpose: to understand and help restore nature on Ulkokrunni.

The goal of our fieldwork was to support ongoing habitat restoration on the island and to test different environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling methods for their usefulness in routine biodiversity monitoring of Northern habitats. We tested these eDNA sampling methods across a range of microhabitats: moss and crowberry from sunlit patches, birch and pine from the canopy, and even spiders and their webs. Sequencing these samples will help map species across the island without having to track each organism in the field.

In parallel, we also contributed to the restoration work, stacking cut birch and aspen into piles that will be burnt in winter to bring sunlight back to the eskers. These sandy ridges, once open and sunlit, are now being closed in by forest. Clearing them is the only way to keep the specialist plants, insects and nesting birds that depend on open ground. In the coming years, we will work closely with the ongoing habitat restoration project to strengthen collaboration between citizen-led conservation and university research. Our goal is to help bridge the gap between science, society, and policy, and to contribute to practical guidelines for using eDNA in biodiversity monitoring across varied habitats.

This work matters beyond Ulkokrunni’s shores. Europe is now in its restoration decade. The EU’s Nature Restoration Law mandates restoration on at least 20 % of land and sea by 2030. Both the island and SAFIRE’s contribution are modest in scale but are part of this broader shift, and driven by the same sense of urgency.

Leave a comment