The Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans) is nocturnal and has furry glide membranes between its limbs (the patagium), allowing it to glide from tree to tree and almost never touch the ground. It is the only species of the flying squirrel family which is currently found in Europe and needs mixed old-growth forests to survive. The foliage of conifers and cavities in the trunks provide cover year around while the flying squirrel is feeding on leaves and catkins of birch and aspen. But these elusive gliders can live closer than you may think: Flying squirrels live in the backyards and parks of some cities in Finland too, such as Vaasa, Helsinki or Jyväskylä.

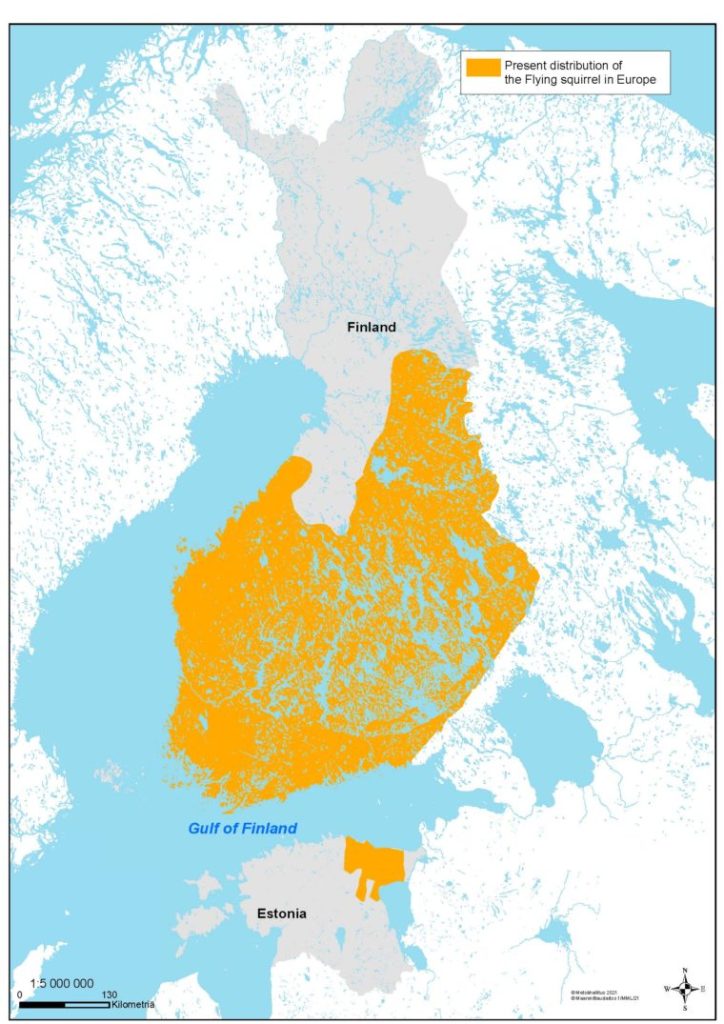

Over the last century, the flying squirrel went extinct in several European countries. Today, it is only found in a few sites in Estonia and throughout parts of central and south Finland. By law, they are heavily protected within the EU and given its large population size, Finland holds special conservation responsibilities. However, populations are still decreasing, mostly due to habitat loss and fragmentation through extensive forestry. Recent changes in conservation and forestry legislations made the execution of an effective protection of the small native rodent even harder.

At the same time, not much is known about the population structure of the flying squirrels in Finland. Are they too isolated from each other? How high is the genetic diversity or is there inbreeding? Can flying squirrels still find breeding mates over growing distances, across streets and through heavily used forests? Is the risk of multiple local extinction events and the eventual collapse of the Finnish population higher than ever?

To understand and eventually help this elusive but iconic species of the Finnish forests, we first will investigate the genetic landscape of the Finnish population, looking for patterns in population structure or signs of genetic erosion. At the moment we are preparing a chromosome-level reference genome as the basis for further studies nobody has done before. Road kills and museum specimens from all over the current distribution range in Finland are used to sequence as many individuals as possible. With partly historical specimens from museum collections in Helsinki, Jyväskylä and Oulu, we might get an insight of how human influence has changed the flying squirrel population until today. All those dead individuals will help to reveal the population structure and hopefully protect their living relatives in the wild.

With all this data we plan not only to inform stakeholders about the situation of flying squirrel to improve the legal situation, but also to develop a molecular method to carry out genetic monitoring using non-invasive sampled droppings in the future. With a more detailed resolution of the genetic patterns in individuals we hope to identify the exact barriers in both urban and natural landscapes which hinder dispersal, but also find connections that successfully allow for free movement.

We can only effectively protect this elusive species, if we increase our knowledge about it. Modern genomics can provide such crucial information. Let’s hope it is not too late for the small ghosts gliding through the Finnish forests…

Repost from the 5th September 2023

Leave a reply to Martin Grethlein Cancel reply